Introduction

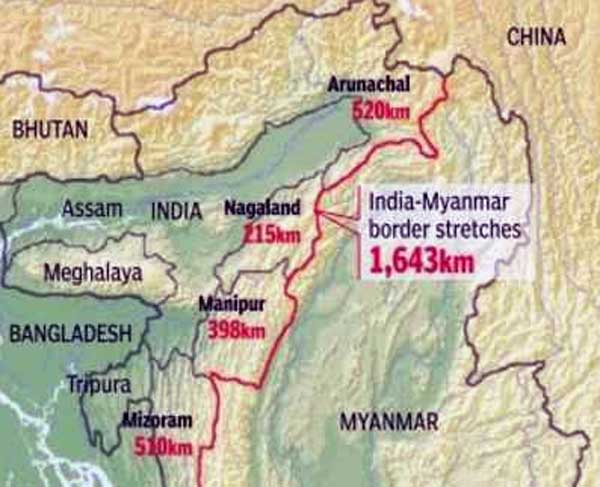

In February 2024, the Union Home Minister, Amit Shah, announced that the Indian government would construct a fence along the border with Myanmar. Additionally, the Government decided to scrap the Free Movement Regime (FMR) along the Myanmar border to ensure the internal security of India. The India-Myanmar border passes through the states of Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh. Broadly speaking, India and Myanmar share an unfenced 1,643-km-long border. A 1968 government notification limited the free movement of people up to 40 km on either side of the border, which was further reduced to 16 km in 2004.1 From the following points, we can understand this issue comprehensively.

Historical Background

Myanmar holds significant importance among the Southeast Asian countries that share borders with India on the eastern side. According to The Treaty of Yandabo of 1826, Myanmar (Burma) became a part of British India. However, in 1937, it was separated from India and made a separate state by the British government. The history of Indo-Myanmar relations can be fruitfully traced since 1948. The principles of Myanmar’s foreign policy were similar to those of India, and hence the historical, cultural, and economic links further provided a helpful basis for the development of Indo-Myanmar friendship and cooperation.2 However, as Myanmar, currently under military dictatorship, is facing the rebellion of ethnic armed groups and pro-democracy forces, there has been a significant influx of people from Myanmar to bordering Indian states.

Free Movement Regime (FMR)

The only stretch of the border where the Centre has erected a fence is on a 10 km stretch at Moreh in Manipur’s Tengnoupal district, a project that was sanctioned as far back as 2003.3 Furthermore, The Free Movement Regime (FMR) was implemented in 2018 as a part of India’s Act East policy, allowing cross-border movement up to 16 km without a visa. The agreement was brought about to facilitate local border trade, improve access to education and healthcare for border residents, and strengthen diplomatic ties. Under the agreement, individuals were also allowed up to two weeks in the neighboring country by getting a one-year border pass.

Border Management

The involvement of the border population in border management is essential. The needs of people living around borders are unique. Often, they live in remote locations with poor connectivity. They also cross to the other side sometimes, simply because the economic opportunities are better. Border crossings and customs checkpoints should be neat, spacious, and have a pleasant ambiance. All crossings should be recorded. Modern technologies can be used for this purpose.

Challenges in Border Fencing

Border fencing is an expensive business. Fencing the India-Myanmar border, which runs along treacherous territory dotted with dense forests, hills, and rivers, would be even more costly. New Delhi has so far spent more than Rs. 35 crore on fencing just 10km of the Manipur-Myanmar border. Extrapolating and fencing the rest of the border would incur an astronomical cost of more than Rs. 5,700 crores to the exchequer.4 The fences need to be designed keeping in mind the terrain and adequate floodlighting has to be provided as well. Constructing the fence is not enough; it must be guarded by border-guarding forces. There must be adequate infrastructure for their deployment, which includes barracks, watchtowers, roads, shelters, etc. The logistics of maintaining guarding forces on the fences is extremely complex and expensive. At several places, the only way to reach remotely deployed fences is by helicopter, as roads do not exist.5

Stance of State Governments

Nagaland and Mizoram have opposed the central government’s decision to fence the border because of the historical ties of the Zo ethnicity people who live in Mizoram and Chin hills of Myanmar. On the other hand, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh have supported the central government’s decision over the security issues of the border area they face. Manipur, in particular, grapples with the repercussions of the Myanmar conflict, witnessing ethnic violence and drug smuggling activities. The nexus between the civil war in Myanmar and the surge in drug smuggling exacerbates security concerns, prompting calls for decisive action.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while India and Myanmar historically enjoy positive relations, addressing security concerns along the border is essential. However, before implementing blanket border fencing and scrapping the FMR, the Indian government must consult with border communities. Their insights can offer valuable perspectives on the potential impacts of such measures on their lives. Balancing security needs with the rights and needs of border residents is most important. A collaborative approach, involving stakeholders from both sides, can lead to more effective and sustainable border management strategies while preserving bilateral relations.

References:

- Singh, V. (2024). India suspends Free Movement Regime with Myanmar. The Hindu. Retrieved from https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-suspends-free-movement-regime-with-myanmar/article67824429.ece

- Jayapalan, N. (2001). Foreign policy of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist.

- Choudhary, A. (2024). Walls in the Era of Bridges: The Many Costs of Fencing the India-Myanmar Border. Issue Brief, Issue No. 3. Retrieved from https://snu.edu.in/centres/centre-of-excellence-for-himalayan-studies/research/walls-in-the-era-of-bridges-the-many-costs-of-fencing-the-india-myanmar-border/

- Ibid.

- Gupta, A. (2018). How India manages its national security. Penguin Random House India Private.

Leave a comment